EXHIBITION - TOLD UNTOLD - Kolkata Show

Told Untold by Samir Aich

Curator’s note by Jyotirmoy Bhattacharya

There’s only one difference between a madman and me. The madman thinks he is sane. I know I am mad — Salvador Dali

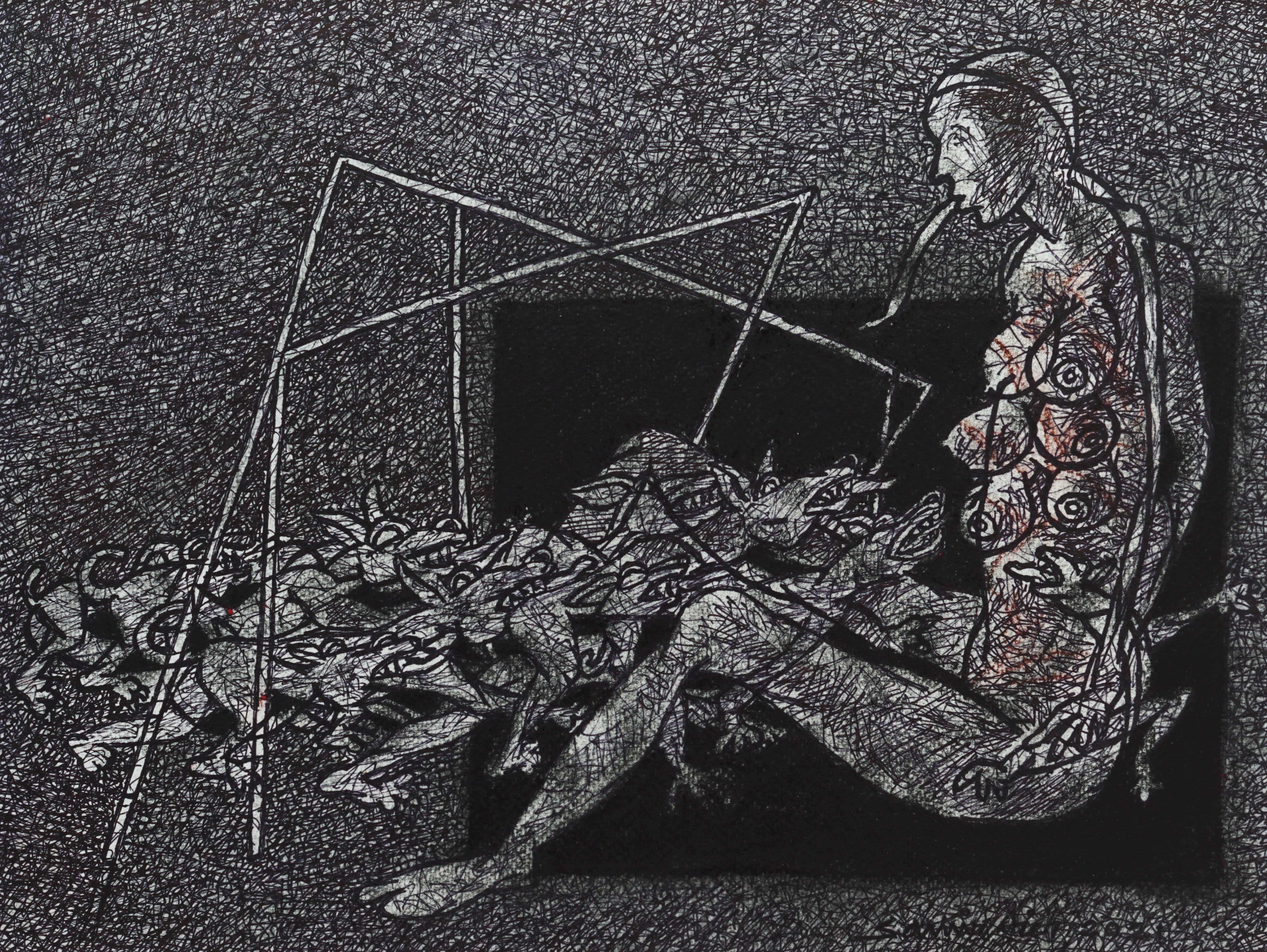

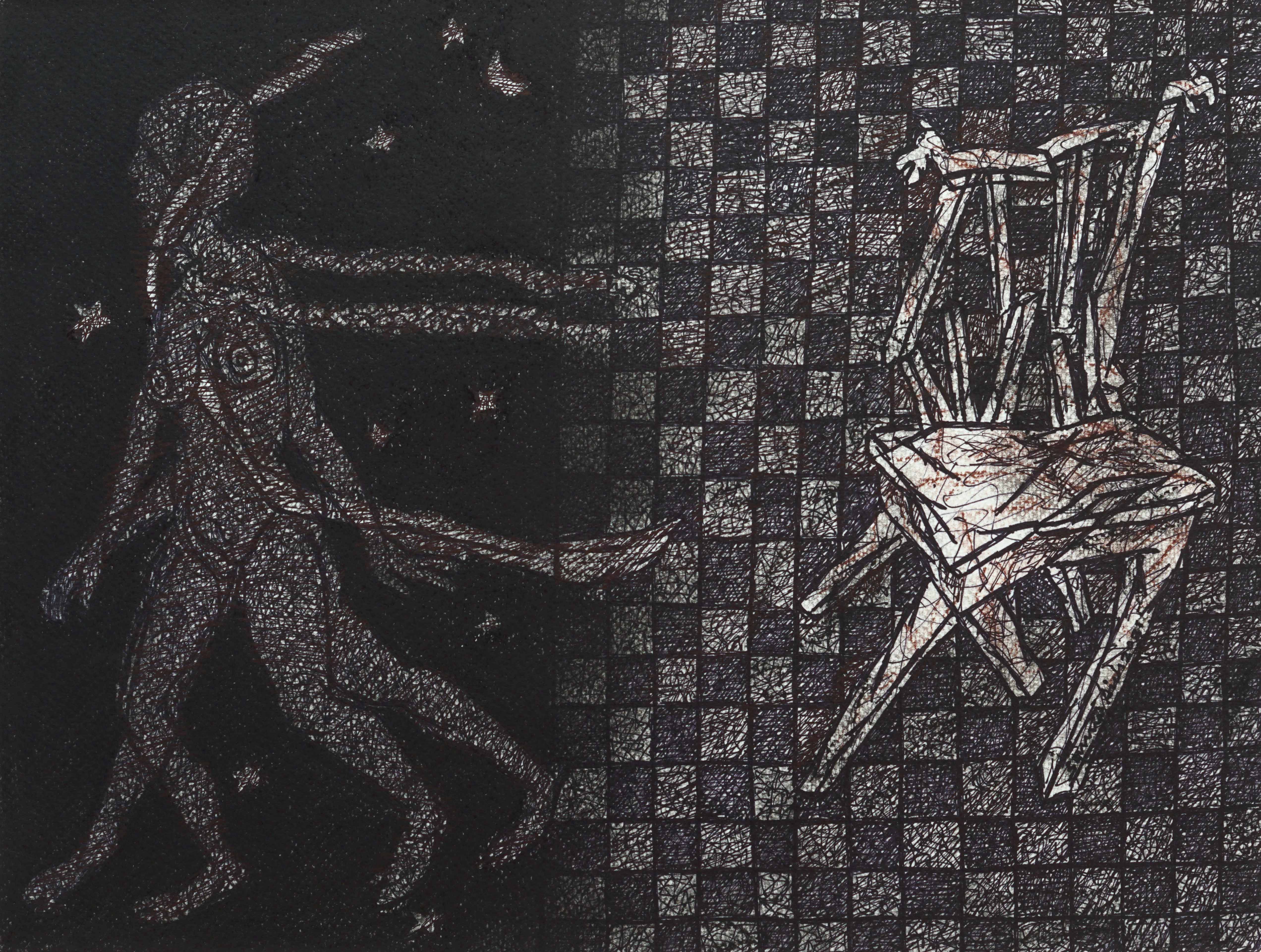

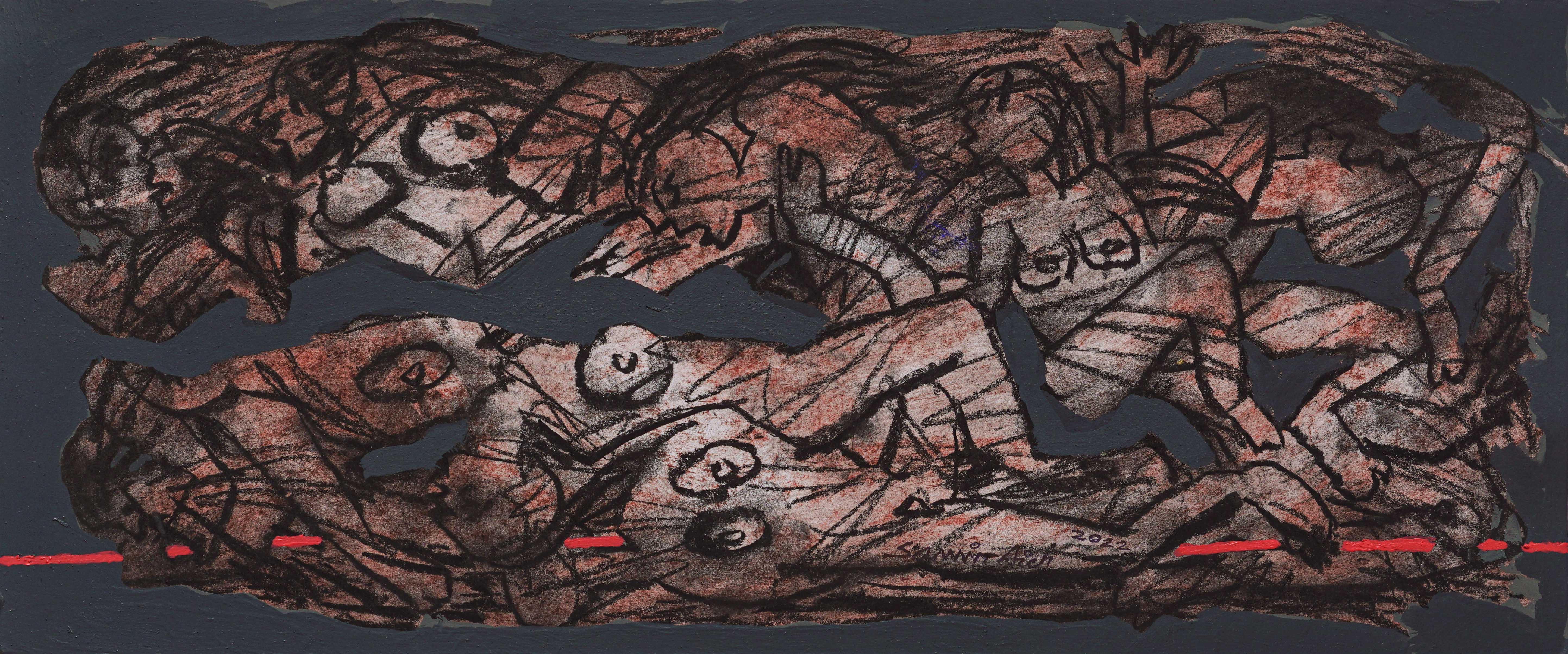

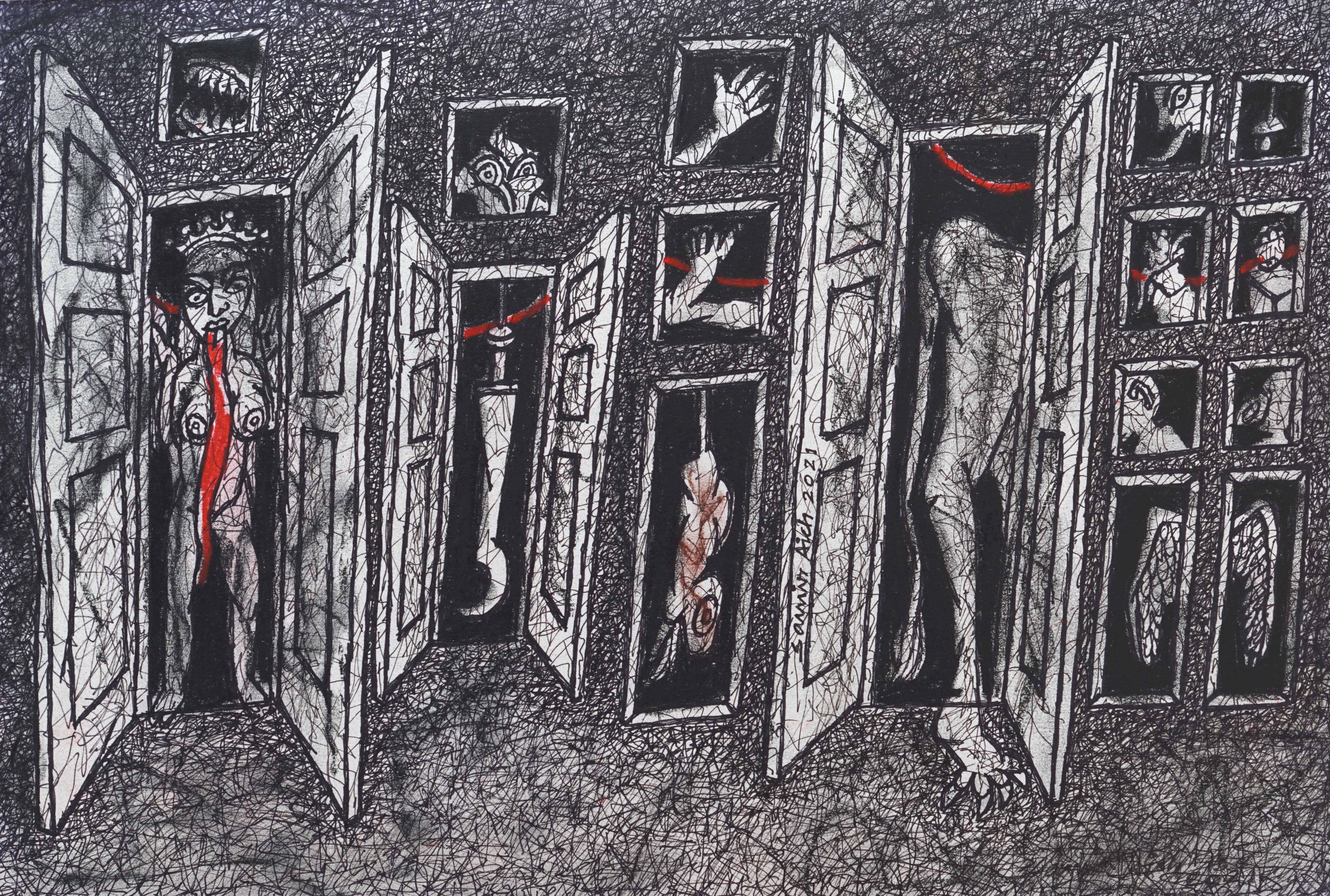

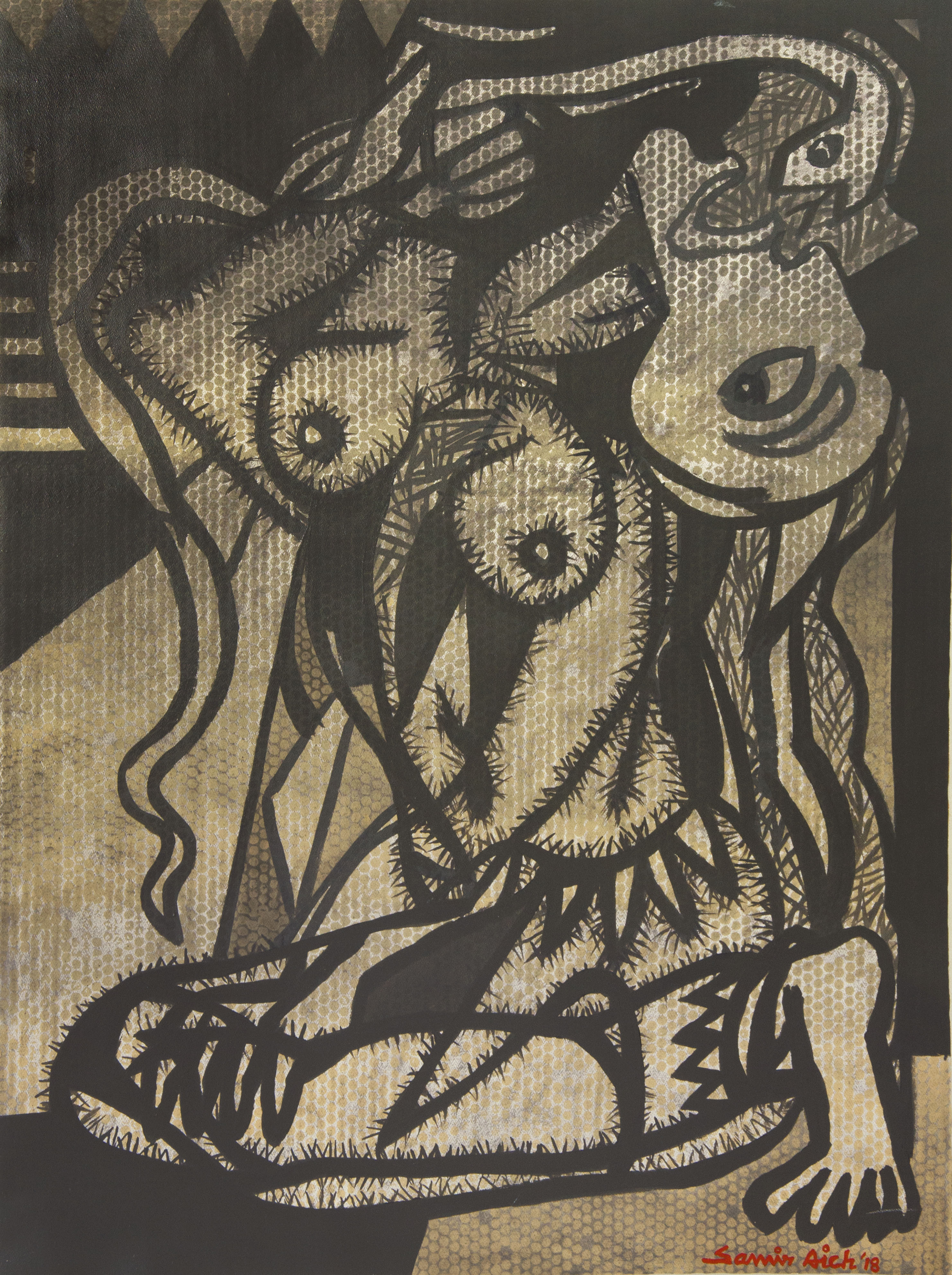

These lines haunt me when I see the surrealistic rendering of crippled society on Samir Aich’s canvases. From primordial to now, paradise to perdition, divine or the godless, virtuous or evil — the paintings are vessels of powerful ideas born out of dilemmas spawned by the collision of these real yet strange forces, the colours ignited by the transition of time. Paradoxically, the expression of his thoughts is as compelling as the seeming urgency to obliterate them in a swipe. Yet, Samir Aich’s subjects conjure the very real struggles that we experience in the loop of indestructible creation. The primitive beasts that repeatedly show up in his paintings are scathing brooders overseeing humanity’s self-imposed wounds from time immemorial. The artist’s hollow men have no wants or desires of their own, yet they are out to snuff out the last filament of thought, feeling or joy left in the world — they betray the underlying psychology of the artist’s perception of society. Perhaps, it’s not possible to detoxify society. But the toxins can be clearly delineated. So, we see these impressive essays that mirror the artist’s clear-eyed views. Somehow, they lift our senses even in a heap of twisted pain.

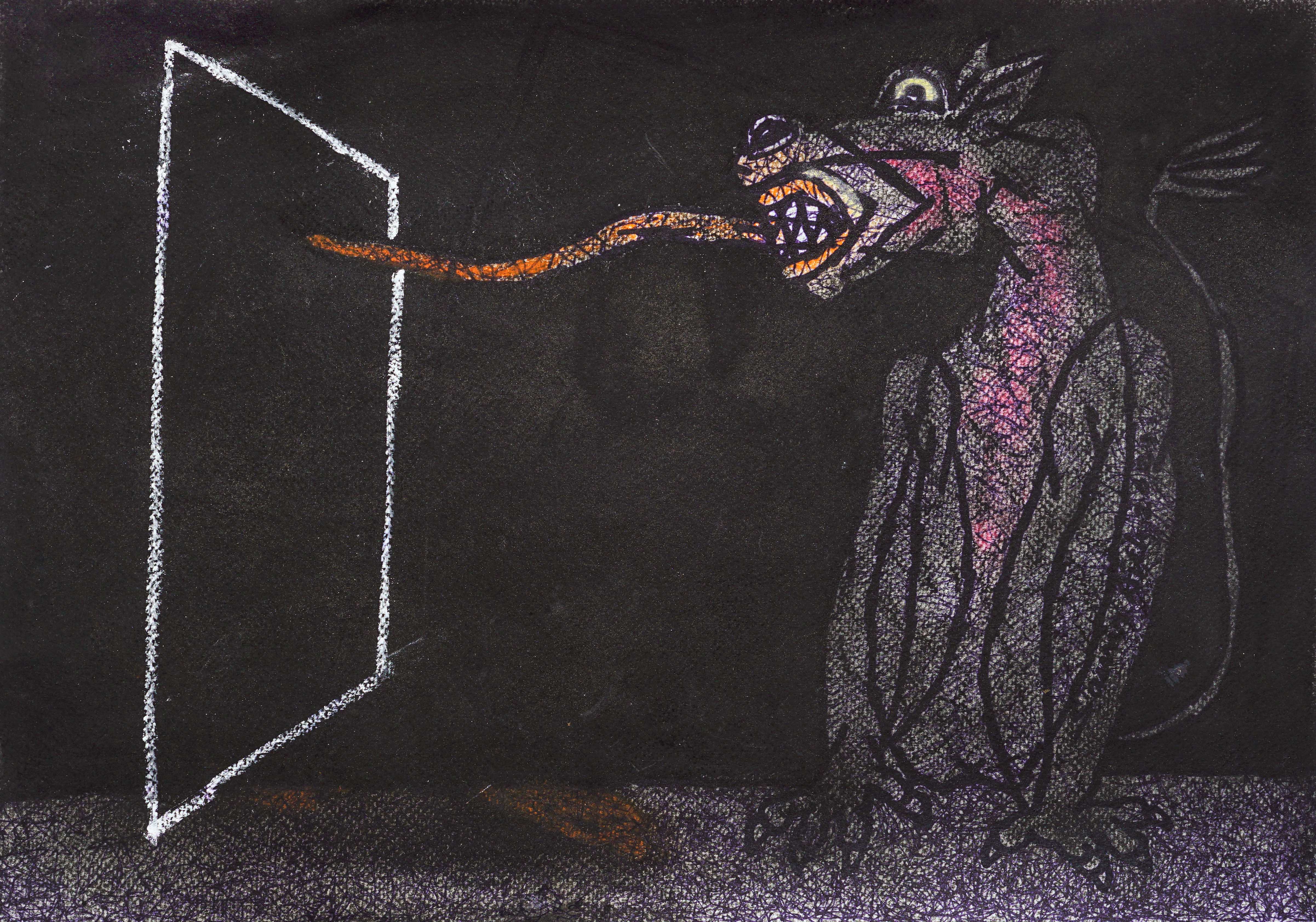

Aich skillfully presents humanity’s savage instincts through his subjects. The structure and layout of his paintings create a deliberate drama that metaphorizes society. In 1937, Picasso had said about his painting, Guenica: ‘A painting is not made to decorate apartments. It is an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.” The architecture of Samir Aich’s paintings seems to support that sentiment. I am as drawn to his portrayals of a bed in a concentration camp or the howling void of a hospital amid a pandemic, as I am to the scorched, bare-bodied beings that peep out of fissures. The emperor’s throne wobbles on a chessboard; a lascivious creature recoils in the glare of fearless eyes; a grievously-wounded Jatayu lies on the floor — these are not just eloquent tropes. They force us to question our permanent state of defeat, wonder how many more blows we can take. So, I see these paintings in a different light altogether.

Samir Aich’s paintings hurl tough questions at the viewer on behalf of the exploited, people whose dreams have been crushed. By bluntly projecting cruel power in the form of a famished leopard, slobbering tongue out, in a swarm of humans, the artist is saying, ‘Emperor, where are your clothes?’

The artist’s paintings remind me of Peter Paul Reubens’ Consequences of War. Also, of Salvador Dali’s The Face of War; and John Nash’s Over the Top. My mind goes back to Francisco Goya’s The Third of May, 1808 or even Umberto Boccioni’s Charge of the Lancers. It also transports me to Samir Aich’s own painting on the battle at Kurukshetra.

The danse macabre does not weigh me down, rather its stinging beauty exhilarates.

.jpg)